2025-04-16_23-45-48

Hinatagama, a pottery studio located in Chinzei, Karatsu City, Saga Prefecture, is known for producing exceptional works of Jakatsu Karatsu—a form of Karatsu ware distinguished by its beautifully crackled glaze patterns.

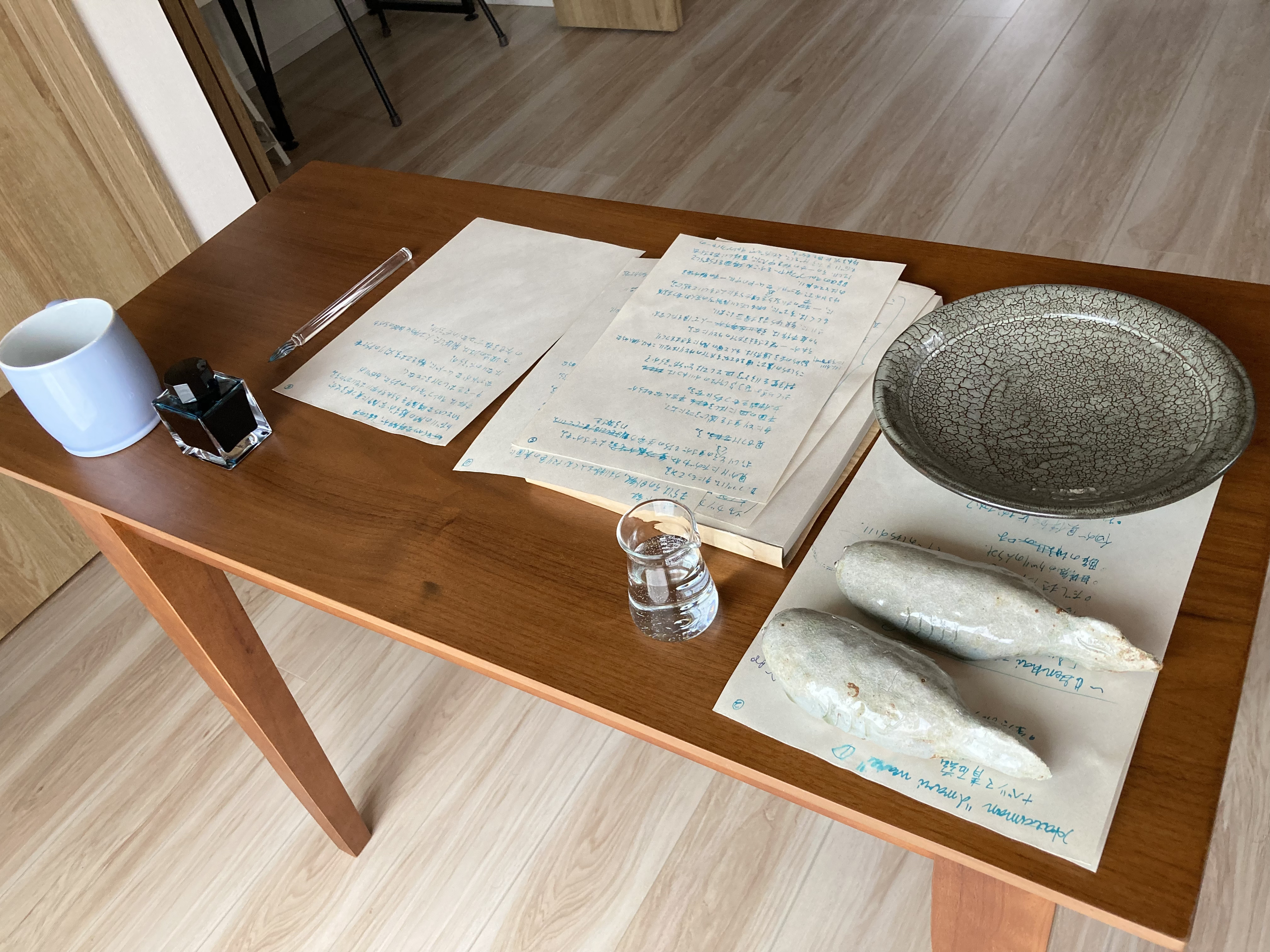

In this article, I will share my experience of holding and appreciating a Jakatsu Karatsu plate that I acquired directly from the studio in 2024, along with reflections on the harmony between nature and craftsmanship that lies behind its creation.

Surface and Depth

There are a few creations that allow us to feel the inside simply by looking at the surface. When we see a painting of train tracks, we may imagine a town at the end of the line. But we cannot see or feel a town that is not depicted.

Pottery, however, is different. It consists of clay, which shapes the form, and glaze, which covers the surface. The interaction of these two elements leads to endless variety. By observing the brushstrokes and glaze expressions on a plate, one can often sense the qualities of the clay that lies beneath.

The Jakatsu Karatsu plate I own is no exception. By holding it in my hands and gazing at it, I can sense the character of the earth that forms its body. Hinatagama, based in Chinzei, produces many masterful examples of Jakatsu Karatsu, a distinguished branch of Karatsu ware.

Karatsu ware refers to ceramics made primarily in Karatsu City, Saga Prefecture. Its origins date back to the 16th century, giving it a history of over 400 years. In the world of tea, the phrase "Raku first, Hagi second, Karatsu third" attests to its high status among Japan's three great tea bowls.

Various styles of Karatsu ware exist, such as E-Karatsu and Chosen-Karatsu, each marked by the rustic texture of the clay and a quiet aesthetic that is easy to accept and appreciate.

Among them, Jakatsu Karatsu is notable for its glaze, which contains feldspar and creates a patterned network of cracks. This plate was also purchased directly from the studio in 2024.

Let us begin by appreciating the surface.

The lead-colored surface, tinged with pale green, is streaked with dark brown patterns. These patterns resemble thorny cracks, appearing both cohesive and irregular. Overall, they seem alive, like a mass of cells proliferating within a living organism.

Even with the same technique, no two pieces will ever be identical. The beauty that emerges from entrusting part of the process to nature may reflect the deep-rooted reverence for nature in Japanese culture.

In general, the fusion of the artificial and the natural can easily lead to chaos. Therefore, the artisan's dialogue with nature—through hands, ears, and eyes—is crucial. If either the natural or the human element asserts itself too strongly, the piece becomes unbalanced. Perhaps this is the essence of the Japanese saying: "Harmony is to be valued."

In other words, it is the harmony between manmade and natural forces.

Weight and Presence

Now, I hold the plate in my hands.

It carries the weight one would expect from its appearance. This density conveys the vitality of the surface patterns. The act of feeling its weight gives the flat, crackled design a sense of three-dimensionality.

Would such a plate, with its deep fissures, be suitable for presenting cuisine? In highly formal settings, where polished elegance and flawless presentation are expected, this piece might feel too intense or commanding. While a subtle irregularity might help ease tension and spark a shared smile, this plate feels more like a dignified work—too elevated for formal hospitality.

In that sense, this plate is well suited for solitary moments, like savoring sake alone.

Alternatively, it may suit an intimate gathering of close friends, offering a subtle axis that unites the mood.

Imagine a group of old friends gathered around a BBQ campfire. Stories flow around the central flame, the conversation expands, and then eyes return to the flickering fire. Those small, quiet moments between stories become cherished memories.

In the same way, this plate, like a campfire, does not impose a theme or topic. Instead, it offers a quiet axis around which warmth and dialogue can revolve.

This effect, I believe, arises from the aforementioned harmony between the natural and the crafted.

Clay and Origin

Let us now look at the back of the plate.

At its center lies the reddish clay that forms its core.

Seeing it, touching it, and sensing the lifelike three-dimensionality of the form, I could feel a force pulsing within—not warmth or gentleness, but the fierce, surging vitality of clay itself.

What I held was clay. Before that, it was stone. And before that, it was molten lava churning deep underground.

The life force I had been sensing was the heartbeat of the earth.

At the same time, the fact that this inner vitality is not forced upon the viewer, but quietly embodied in the piece, from the very first glance at the surface, is a testament to the artisan's masterful technique.

Reflection and Rediscovery

Looking again at the surface after seeing the interior, what I now see is no longer merely the lead-colored glaze with pale green tones, nor the thorn-like crackle patterns.

I see the history of matter—organic and inorganic—producing minerals and nurturing life.

By viewing the surface and imagining the interior, then seeing the interior and sensing the surface, and finally seeing the whole piece anew, one may come to understand the essence of the work.

To share nostalgic memories while gazing at the visible flames of a campfire—this act may not be so different from writing this reflection based on the plate before me.

I will refrain from elaborating further on that thought, lest it become too forceful or unbalanced.

Nonetheless, I urge you to visit the studio and experience Jakatsu Karatsu for yourself.